I’ve been paying close attention to compute networks for a while now.

Most conversations rarely explain why so few of these networks are meaningfully decentralized (even as they generate sizeable revenue), or why enterprise adoption keeps stalling.

So this deep dive is about what happens when a sharp team focuses on the actual core problem and creates an innovative business model around it. Yotta Labs is turning unreliable machines into something that behaves predictably enough to support serious AI workloads.

If you care about AI infrastructure and what it would actually take for decentralized compute to move past demos and into production, this is a useful case study.

This is not a vision piece. It is a systems story.

Let’s dive in.

Here is my bet:

The most important infrastructure company in decentralized compute will look less like a GPU marketplace and more like an operating system.

I had that thought as I was scrolling through YouTube at the airport while waiting for 4-hour flight. A video recommendation caught my eye.

PewDiePie had uploaded a video titled “STOP. Using AI Right Now.” It already had millions of views. Curiosity won, and I clicked it.

The video itself was mostly spectacle. A walkthrough of how he built a monstrous PC with nine GPUs, bifurcated PCIe lanes, and enough DIY electrical improvisation to make an electrician flinch. All to run large open-source models locally.

Then he mentioned something I did not expect, almost in passing.

He’d been using that machine to contribute compute to protein-folding simulations for medical research, running decentralized workloads overnight and tracking his rank on a “charity leaderboard.”

One of the most-subscribed YouTube channels on Earth explaining decentralized compute to a 110-million–subscriber audience? Not something I had on my bingo card.

This made me think:

If PewDiePie is talking about decentralized compute, has it gone mainstream?

Culturally, maybe. Technically, no.

What he is doing fits perfectly with the kind of volunteer workloads (like Folding@Home) that have existed for years: tolerant of slowness and faults and inconsistent machines. They’re the ideal use case for decentralized compute.

But modern AI is not. It needs something more reliable.

The Gap Between Awareness and Performance

In my Open Compute Thesis a few months ago, I wrote:

The next phase of AI will demand more compute than any single provider can supply. Even with NVIDIA scaling production, the need for GPUs will likely continue to outpace availability, driven by AI’s expansion across every sector.

Decentralized compute networks are in position to absorb some of that overflow. Not all of it, and not everywhere. But they can serve the margins: workloads hyperscalers can’t support, or won’t price competitively.

I also argued that decentralized compute still has a few bottlenecks that keep it from finding its product-market fit.

A useful way to evaluate any decentralized compute network is to ask three questions, in order:

Coordination: Can globally scattered GPUs be made to behave like a single machine?

Reliability: Can the system deliver predictable performance when nodes drop, or hardware misbehaves?

Developer Experience: Can real teams deploy and operate it without becoming distributed systems experts?

If a system fails early, nothing downstream matters. So while all 3 matter, it’s obvious that one matters more than the others.

Coordination: The Hard Problem

My working forecast is that decentralized compute will not become real infrastructure until coordination is solved. Reliability and developer experience follow. They do not lead.

The reason is structural. GPUs in the wild do not behave like GPUs in a data center. They show up with different VRAM limits, memory bandwidth, network quality, uptime, and failure quirks. They appear and vanish on their own schedule. They sit behind noisy ISPs, consumer routers, and power that flickers when someone turns on the microwave.

In short: Nothing is stable. Nothing is predictable. Nothing is standardized.

Yet, the dominant AI runtimes that hyperscalers rely on (DeepSpeed, Megatron-LM) assume the exact opposite. They want clean links and steady latency. Spread an LLM across a swarm of inconsistent consumer GPUs, and the whole profile craters.

That’s why decentralized compute feels stuck. Performance and serious adoption is not there yet.

If this is ever going to operate at the same reliability tier as AWS, the infrastructure has to make fragmented hardware behave like one reliable machine. That is the hurdle. And that is the opening for Yotta Labs.

Where Yotta Enters the Story

Solving this is a hard engineering and systems-design problem. It is the kind of work you take on only if you get some strange satisfaction from chewing glass. Yotta does.

They realized that if we want decentralized compute to work at scale, you cannot tape it to the existing stack. You have to rebuild the whole AI stack from the ground up. Make heterogeneity your friend, not your enemy.

From the scheduler to the communication layer to the memory optimizer, every part of the Yotta system is engineered to absorb the realities of:

different accelerators (B200s, H100s, 5090s, MI300Xs),

different clouds (AWS, GCP, Lambda, Nebius, etc),

different reliability profiles,

and different networking conditions.

The result is not a new GPU marketplace, but a new coordination layer: a software system that makes scattered imperfect hardware behave like a single, steady cluster for predictable execution of AI jobs.

And this is where the real technical story begins.

Section I: Under The Hood

We get technical in this section, but there is a good payoff. By the end, you will have a clearer picture of how training and inference actually work!

If decentralizing compute were as easy as tossing a pile of GPUs into a global marketplace, we would not still be talking about it. But here we are.

The Core Challenge: Four Interdependent Constraints

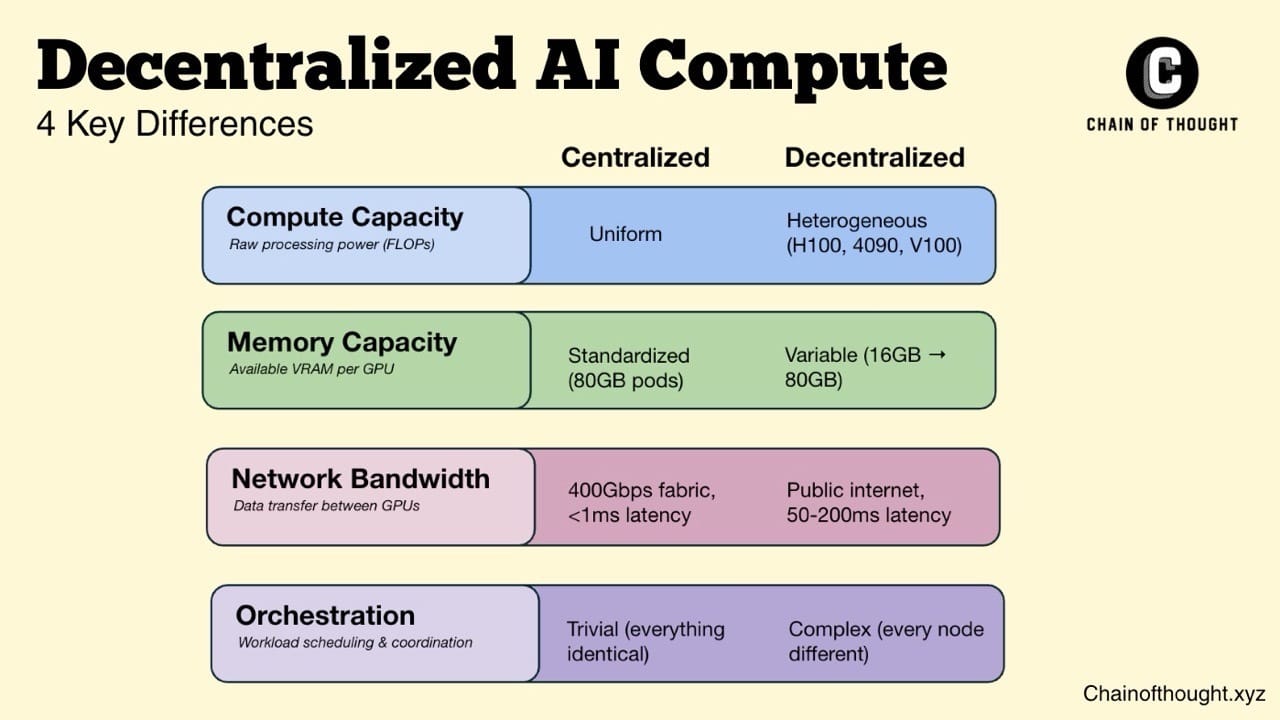

Every distributed AI system operates within four fundamental constraints: Compute, Memory, Bandwidth, and Orchestration.

In centralized infrastructure, these constraints are trivial to manage because everything is uniform. In decentralized infrastructure, they become the primary engineering challenge:

Heterogeneity breaks our common assumptions. A 16GB consumer GPU and an 80GB H100 are not interchangeable. Cross-region latency is not predictable.

This is the coordination problem at its core: making globally scattered, mismatched hardware perform like a coherent system without sacrificing throughput.

Most decentralized networks avoid the issue by only accepting workloads that can survive failure and delay. This heavily limits its addressable market.

Yotta is aiming at a larger target: make decentralized infrastructure usable for compute-intensive, performance-critical AI workloads that can tolerate bounded latency under explicit SLAs (Service Level Agreements).

Ultra-low latency remains the domain of centralized clouds. But not every AI workload needs millisecond-perfect response times. As long as performance stays within agreed service levels, many teams are willing to trade latency headroom for capacity, flexibility, and dramatically lower cost.

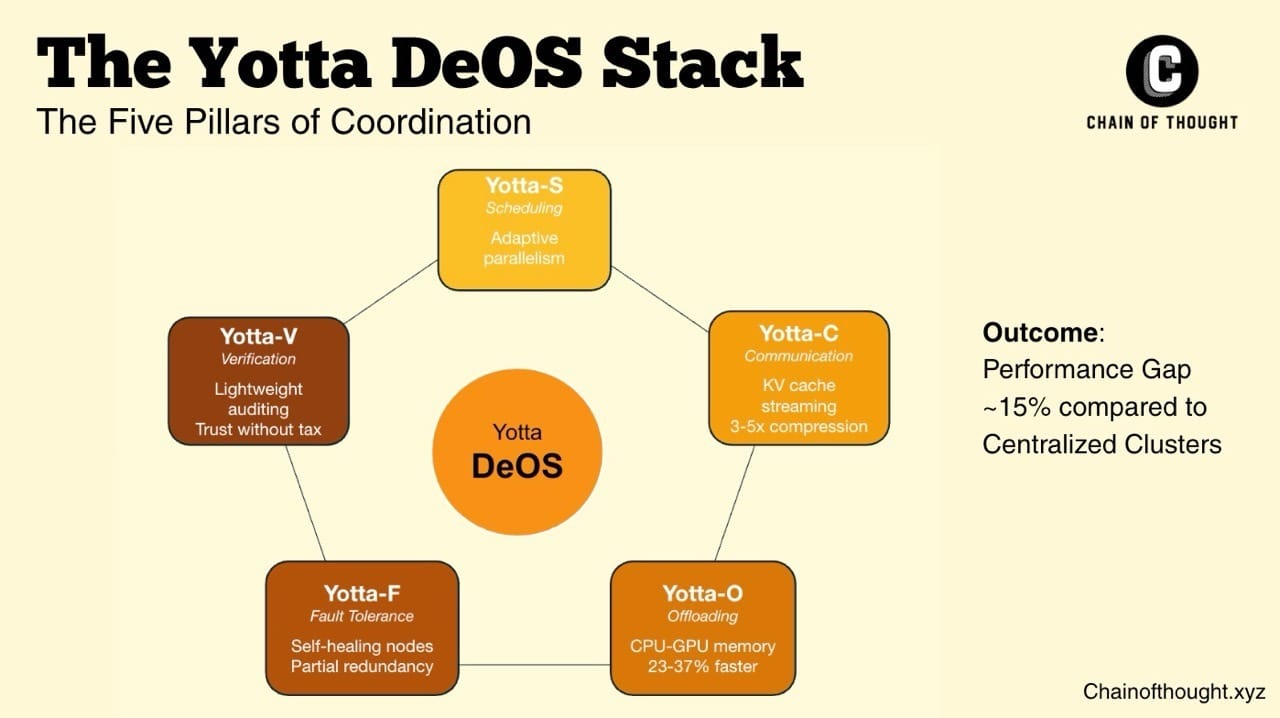

Yotta's Solution: A Five-Component Operating System

The Yotta OS (DeOS) is structured around five interdependent components, each targeting a specific dimension of the coordination problem:

Yotta-S (Scheduling)

Yotta-C (Communication)

Yotta-O (Offloading)

Yotta-F (Fault Tolerance)

Yotta-V (Verification)

Let’s break down how Yotta actually makes this work across the core pillars of decentralized compute.

Pillar #1: Making Heterogeneous Hardware Act Like a Team

An 80GB H100 in Manila, a 24GB RTX 4090 card in Toronto, and a 180GB B200 in Frankfurt all have different strengths, weaknesses, and network connections. Yotta’s first pillar is about embracing this mess.

Yotta-S: The Scheduler That Rewrites the Playbook

When running AI workloads, most systems try to park an entire model on a set of GPUs and hope the hardware behaves.

Yotta takes a different path. It breaks the model into structured pieces and assigns each piece to the type of GPU best suited for it.

To make this intuitive, it helps to stop thinking about parallelism as a single trick and start thinking about it as a five-dimensional design space.

In modern AI infrastructure, practitioners often refer to this as 5D parallelism: five different ways to slice a model or its workload so more GPUs can work at once.

Data parallelism

Data parallelism is the most familiar form. Each GPU holds a full copy of the model, but processes a different slice of the input data. Afterward, results are synchronized so all replicas stay consistent. This works best when GPUs are close together and communication is fast, typically within a single data center or site.

Pipeline parallelism:

Pipeline parallelism treats the model like an assembly line. Instead of running the full model on one machine, the model is split into stages, with each GPU responsible for a different segment. As one stage processes a microbatch, the next stage is already working on the previous one, keeping the system busy end-to-end.

This approach is especially effective across sites, where bandwidth is limited and latency is unavoidable. By minimizing the amount of data that needs to move between stages, pipeline parallelism allows Yotta to spread a single model across geographically distributed hardwareTensor parallelism

Instead of duplicating the model, it splits large internal computations across GPUs. Each device handles part of the calculation, and the partial results are stitched back together. This is what allows very large models to run even when no single GPU has enough memory to hold them.Sequence parallelism:

Sequence parallelism is a refinement of tensor parallelism, designed for long contexts. Rather than splitting weights or batches, it splits the token sequence itself. Each GPU handles a slice of the sequence, which is particularly useful for attention and normalization layers that struggle with very long inputs. As context windows grow, this dimension becomes increasingly important.Expert parallelism

Finally, expert parallelism applies to Mixture-of-Experts models, which are architectures where only a small subset of the model’s parameters, or “experts,” are activated for each input, allowing models to scale in size without requiring every GPU to compute every token.

Yotta distributes different experts across GPUs and routes tokens dynamically, so each device only computes what it’s responsible for. The result is massive model capacity without linear increases in compute cost.

Yotta did not invent these techniques. But the clever part is adaptive parallelism, where it treats them as interchangeable tools rather than fixed architectural choices. Yotta looks at every layer of the model and asks:

Is this operation slow because it requires a lot of math (computation or FLOPs), or because it needs to move a lot of data?

Some layers are compute-heavy (algebra, math). Others are memory-hungry. Yotta picks the parallelism strategy that lets the GPU spend less time waiting and more time working.

This makes Yotta-S behave less like a static runtime and more like an AI-first compiler for distributed systems, optimizing execution across whatever hardware is available.

In early internal tests across four AWS regions measured by training throughput (effective FLOPs), Yotta achieved 2.8x higher throughput than DeepSpeed, 1.6x higher throughput than Megatron, and 21% higher throughput than the strongest decentralized baseline (SHE).

Quick detour: What are DeepSpeed and Megatron? Why does beating them matter?

DeepSpeed (by Microsoft) and Megatron-LM (by NVIDIA) are the gold-standard frameworks for training giant AI models on uniform data center GPU clusters.

They are ultra-optimized, specializing in parallelism tricks and memory partitioning. They assume identical GPUs, fast links, and tightly controlled conditions.

So when Yotta outperforms established systems like DeepSpeed, Megatron, and even the best decentralized baseline (SHE), it sends a clear signal: decentralized compute doesn’t have to be slow. With the right scheduling and orchestration, a decentralized system can approach the performance of the fastest centralized frameworks in production today.

What’s more striking is how close the gap has become. Even with traffic spanning multiple continents, Yotta’s decentralized setup runs within ~15% of a fully centralized cluster.

This is where the economics turn.

Once decentralized compute is close enough on throughput and effective FLOPS, the inefficiency stops being decisive. Compute no longer has to sit in a single cluster. Capacity becomes elastic, jobs spill across regions instead of waiting in queues, and idle resources finally get used.

Cost is the real advantage. Power prices vary sharply by geography, and large pools of compute sit underutilized. Reaching across regions lets workloads run where electricity is cheaper, which translates directly into more performance per dollar.

At scale, a small performance penalty is easily offset by lower energy costs and higher availability. Flexibility matters more than raw speed.

The Prefill/Decode Split: A Practical Superpower

When you ask ChatGPT a question, it isn’t doing one continuous computation. It switches between two very different phases:

Prefill: The model reads your entire prompt and builds up all the internal context it needs.

This stage touches every layer of the network, consumes the most memory and bandwidth, and determines how long you wait before the model outputs its first token.Decode: Once the context is built, the model enters a loop where it produces tokens one at a time.

Each step reuses the stored context (KV cache), runs much less computation, and can run on slower hardware. More importantly, the decode phase is inherently sequential. Each token depends on the one before it, which makes it difficult to parallelize.

Most frameworks run these together on the same GPU. Yotta doesn’t.

Yotta S pushes prefill to the strongest GPUs and hands decode to weaker ones, which means:

High-end GPUs (H100s, B200/300) handle the expensive “big thinking”

Cheap GPUs (consumer cards, L40s, RTX cards) handle the repetitive but sequential “writing the next word”

Turns out, this is quite effective in a global network.

A weak GPU can still be productive, the strong GPU isn’t dragged down, and overall throughput jumps significantly.

But splitting workloads across the Internet creates a new issue: moving the model’s “working memory” between nodes, clusters and regions.

When an LLM processes text, it stores intermediate calculations so it doesn’t have to recompute them every time. That’s the KV cache. Think of the KV cache as the model’s short-term memory. And it can get huge. A single request on a 66B model can produce over a gigabyte of data that must be stored in memory.

Moving it poorly is like forcing a human to rewrite their notes between every sentence. This is why communication strategy matters as much as raw compute.

Sending gigabytes of working memory across long-distance internet connections between regions (i.e. the WAN links), is slow and unreliable. It’s one bad hop away from erasing any speedup.

This is the problem the next two components are designed to solve.

Yotta-C: Hiding Internet Latency

In most distributed inference systems, moving the KV cache becomes the fatal bottleneck. You either:

send the whole cache in one huge transfer and stall everything, or

avoid distributing inference altogether because the communication cost destroys any gains

Yotta does neither.

Instead of treating communication as a single, heavy operation, Yotta-C breaks the KV cache into many small pieces and streams them continuously while computation is still happening.

It is the difference between waiting for a single freight truck to arrive vs. running a conveyor belt that feeds items in motion

Other runtimes could, in theory, attempt this, but making it work across the open internet (with latency spikes, packet jitter, and heterogeneous GPUs) is extremely hard. Yotta’s scheduler and runtime are already built around this communication pattern, which is why the approach holds up in practice.

Continuous streaming changes the rules in several important ways:

GPUs don’t stall.

When one chunk is still traveling over a slower network path, another chunk has already arrived and is being processed.Compute and communication overlap.

The system keeps making progress even when the network is imperfect (the internet is always imperfect)Small chunks tame tail latency.

If one packet is delayed, it slows down only a tiny portion of the workload instead of freezing the entire job.

To push this further, Yotta-C applies a mathematical compression method (SVD) to the KV cache, shrinking it by 3–5× and cutting cross-region communication volume by over 90%.

This means:

fewer bytes traveling across long-haul links,

faster inter-region transfers,

and more headroom to use cheaper, slower GPUs without slowing the system down.

When streaming, compression, and scheduling work together, a key shift happens:

Network latency stops dominating the architecture.

The internet, usually the biggest bottleneck in decentralized compute, becomes something the system effectively hides. Yotta reduces the “internet penalty” so much that distributed inference starts behaving like a centralized cluster.

That’s why this is one of the key reasons Yotta’s system can remain competitive even when GPUs are scattered across continents.

Yotta-O: Memory as Flexible, not Fixed

If Yotta-C solves the problem of shipping data across the internet, Yotta-O tackles a more local but equally restrictive limit: GPU VRAM capacity.

Many consumer GPUs are quite capable in terms of raw compute (FLOPs), yet unusable for large models because a single forward pass can exceed their memory (VRAM). This is why most decentralized compute networks rely only on high-end cards, ignoring huge portions of the global GPU pool.

Yotta-O changes that by refusing to treat VRAM as a hard wall.

Instead, it treats CPU memory as an extension of GPU memory, dynamically deciding:

What tensors must stay resident on the GPU,

what can be temporarily offloaded to CPU RAM, and

and when to move data back without stalling execution.

This approach builds on research led by Yotta’s Chief Scientist Dr. Dong Li, whose 2021 work demonstrated that carefully planned CPU–GPU offloading can extend the effective capacity of smaller GPUs far beyond their VRAM limits. The challenge has always been doing this intelligently and adaptively rather than relying on simplistic rules.

Yotta-O’s key innovation is that it bases its decisions on real measurements of each machine.

It continuously adapts to each machine’s PCIe speed, bus quality, and memory pressure, so the offloading strategy is customized for every GPU, not one-size-fits-all.

This avoids the classic failure mode of static heuristics, which often collapse when hardware varies widely (as it does in decentralized networks).

With this adaptive planner, smaller cards become useful again. A 16GB or 24GB GPU that previously could not run a 30B model now becomes a viable worker in the distributed cluster.

The measured gains from Yotta-O are substantial:

23–37% faster than SwapAdvisor, meaning Yotta’s planner keeps the GPU busy rather than waiting for memory to shuffle.

14% faster than Microsoft’s L2L, one of the strongest offloading systems built for hyperscale environments.

7× less CPU–GPU communication than traditional offloaders, which matters because every extra transfer directly slows down inference.

(Note: These results are based on Yotta’s internal benchmarks. Performance comparisons were measured on specific model sizes, hardware configurations, and workloads, and may vary in real-world deployments.)

Combined with Yotta-C’s latency-hiding and compression, Yotta-O makes sure GPUs with limited VRAM can contribute meaningful throughput instead of sitting on the sidelines.

This widens the pool of hardware that can actually contribute, which is the real unlock for any decentralized compute network trying to grow past a handful of curated datacenter nodes.

Pillar #2: Scaling Models by Using Time, Not Just Hardware

Once Yotta-S and Yotta-C handle parallelism and communication, there’s still one unavoidable constraint left: wide-area latency. Even with clever routing and compression, packets moving across continents take time. No amount of compression removes the speed of light.

The question becomes: How do you keep GPUs busy while they are waiting for the next instruction or data to arrive?

Yotta’s answer is speculative inference but adapted for a decentralized environment. Instead of waiting, the system makes educated guesses and does useful work in advance.

How Speculation Works (Intuitively)

Think of it like a smaller “scout model” that runs slightly ahead of the main LLM, predicting the next few tokens before the primary compute path finishes its work. When the main model catches up:

If the scout guessed correctly, the system accepts multiple tokens in one go.

If it guessed wrong, the system simply rolls back and continues normally.

In centralized clusters, this is mostly a throughput boost. But in decentralized clusters, it's transformative because it fills waiting time.

Speculation keeps distant or slower GPUs busy during what would normally be dead time. Yotta monitors acceptance rates in real time and toggles speculation on or off so that no compute cycles are wasted on unproductive guesses.

Because Yotta-C is already streaming data in small chunks, speculation aligns well with continuous execution. There is always something ready to run, even when the network is slow.

This turns global GPU scatter from a liability into something the runtime can absor,b and it’s one of the reasons Yotta can operate across continents while staying competitive with centralized clusters.

Pillar #3: A Trust Layer Without the Drag

Even with smart scheduling, offloading, and latency-hiding, decentralized compute still has one final unavoidable reality: you’re running workloads on machines you don’t control.

In a centralized data center, trust is implied.

In a global mesh of unknown GPUs, trust has to be earned but without turning verification into a second workload that doubles your compute bill.

This is where Yotta-V and Yotta-F come in.

Yotta-V: Verification That Rides Along With the Model

Most verification systems either run redundant computations (slow and expensive) or rely on TEEs or zero-knowledge proofs that add significant overhead and latency. Neither fits a system that needs to run inference continuously.

Yotta takes a different approach: it embeds verification into the model's normal behavior.

Speculative inference already produces draft tokens that need to be checked. Yotta-V piggybacks on that natural checking mechanism, auditing random positions and comparing expected convergence patterns without running full duplicate passes.

The goal is to make incorrect or malicious behavior statistically detectable and economically irrational, while keeping overhead low enough for real-time inference.

The result is trust that scales with the workload.

Yotta-F: Treating Failure as Routine, Not Exceptional

In an open network, nodes will drop. Connections will stutter. Entire regions can disappear mid-run.

Yotta-F is designed with this assumption baked in.

It keeps the system stable by:

using heartbeats to detect failing nodes quickly,

storing intermediate activations so work can resume instantly, and

applying partial redundancy only where it matters, not everywhere.

This lets the system self-heal and reroute work continuously, rather than collapsing when a single node or region hiccups.

Together, Yotta-V and Yotta-F form the trust and resilience layer that makes the rest of the stack viable.

They allow you to use decentralized hardware without having to constantly babysit. This is the final step in turning a scattered global fleet of mismatched GPUs into a coordinated, fault-tolerant system.

Across tested workloads, this stack delivers multi-fold throughput gains over existing decentralized baselines and narrows the performance gap with centralized clusters to within roughly 15%. Something no decentralized system has achieved before.

From Architecture to Product

Up to this point, we’ve described Yotta largely from the bottom up.

Scheduling systems designed for unreliable networks. Execution layers. Optimizations that make distributed GPUs behave coherently.

All of that is essential. But without stepping back, it’s easy to miss the bigger picture.

Yotta is not one monolithic platform. It is intentionally composed of two distinct products, each addressing a different side of the AI infrastructure problem, and unified by a shared intelligence layer.

Together, they function as an integrated system. Individually, each product stands on its own.

OptimuX, the AI-powered optimization and control plane

The decentralized GPU supply network, the execution and data plane

This separation is deliberate. It explains both how Yotta goes to market today and why its long-term architecture compounds.

Product #1: OptimuX, The Optimization Layer

OptimuX is the layer where Yotta’s architectural ideas become a product.

It functions as an AI-native control plane that continuously optimizes how workloads execute across clouds, regions, and accelerator types. Rather than treating infrastructure decisions as static configurations, OptimuX turns them into real-time, adaptive choices.

For every workload, OptimuX decides:

Which accelerator best fits performance, cost, and reliability requirements

Where the workload should run geographically and across which provider

How precision, batching, and parallelism should adjust under live traffic conditions

When to reroute, reschedule, or proactively recover from impending failures

This is where many of the optimizations described earlier, like routing, failure prediction, and hardware-aware execution, are actually implemented and enforced.

Importantly, OptimuX is decoupled from the underlying compute supply. Enterprises can deploy it to optimize workloads on their existing infrastructure, such as AWS, GCP, Azure, Neo Clouds or on-prem clusters, or apply the same optimization layer to workloads running on Yotta’s decentralized GPU network.

In both cases, OptimuX operates purely as a software control plane, with no requirement to interact with crypto or permissionless systems. That separation is how OptimuX is implemented today and will be offered in the future as a standalone enterprise product, with a SaaS business model.

But optimization systems need to keep getting better, and they only improve by learning from real execution.

Product #2: The Decentralized GPU Supply Network

The second half of Yotta’s system is the decentralized GPU supply network.

This network aggregates GPUs from individuals and micro data centers worldwide. Here is where crypto economics comes into play to incentivize GPU suppliers and bootstrap the network.

Yotta gains direct exposure to how AI workloads behave in the wild, across messy, heterogeneous environments.

Different types of GPUs. Different cooling and power setups. Different memory limits. Different ways things break.

As workloads run across this network, Yotta observes patterns that rarely show up inside clean, uniform data centers. Over time, this creates a growing dataset of how models actually perform in real-world conditions.

In practical terms, this means Yotta learns:

which GPUs deliver the best performance for specific workloads

where bottlenecks emerge under sustained load

how heat, memory pressure, and hardware differences affect reliability

what the real cost–performance tradeoffs look like across device types

This data is aggregated and anonymized and used exclusively to improve Yotta’s optimization layer.

Companies that can construct a real data flywheel have my attention. As I wrote in The Data Republic, the best companies let everyday product usage create a proprietary data asset, pushing marginal data acquisition costs toward zero. Yotta fits that pattern.

The Intelligence Loop

The architecture becomes self-reinforcing.

The data from the decentralized network feeds back into OptimuX, continuously sharpening its optimization models. Hardware selection becomes more precise. Scheduling decisions get sharper. Failure prediction shifts from reactive to proactive.

Optimizations improve performance and reduce costs for users. That attracts more workloads. More workloads generate richer telemetry data across an even broader range of hardware.

The loop compounds:

The optimizer learns from the network.

The network improves the optimizer.

Over time, Yotta builds an intelligence advantage rooted in hardware diversity and real-world execution data. This is not something that can be replicated by simply adding more GPUs to a single data center; it requires operating across the full messiness of global compute.

The Developer Experience: All the Complexity, None of the Pain

What I really like about Yotta is that none of this complexity ever surfaces to the user.

The runtime may be built for the unpredictability of the open internet, but the interface is built for regular developers who just want their workloads to run reliably.

Yotta takes a deliberate approach here:

make the backend radical, and the frontend boring.

hide the machinery so developers only touch a clean, predictable surface.

This matters. Developers interact with a console that feels closer to AWS than to a DePIN project. Polished dashboards, managed endpoints, one-click deployments, clear logs, model APIs, and workflows that fit the mental models developers already have.

For most teams, this is the difference between something that is “interesting” and something that is actually usable.

A great (not just good) developer experience is Yotta’s go-to-market strategy: the smoother the onboarding, the faster real workloads migrate. By meeting developers where they already are, Yotta could remove the switching costs and accelerate adoption.

Once you’re inside the console, the workflow feels instantly familiar:

GPU Pods and VMs let you spin up a single GPU instance, pick your accelerator, attach storage, SSH in, run Jupyter.

Elastic Deployments are the production layer with multi-node clusters, autoscaling, multi-region routing for scalable applications.

Custom Templates allow teams to bring their own environment (PyTorch, JAX, vLLM, fine-tuning stacks), packaged as simple Docker images.

Everything is organized so the mental model becomes: spin up → serve → scale, without needing to understand how the underlying scheduling or communication layers actually work.

The irony is that Yotta may have one of the most complex runtimes in the decentralized compute world, yet one of the simplest developer surfaces. And that’s exactly what’s required if decentralized compute is ever going to move beyond experimentation and into actual adoption.

Section II: The Business

Up to this point, the story has been about how Yotta makes decentralized hardware behave by scheduling smarter, compressing better, offloading intelligently, hiding latency, and verifying correctness without slowing anything down.

These three pillars explain why Yotta can run large models on scattered GPUs without collapsing.

The next natural question:

Where Do Their GPUs Come From?

Today, most of Yotta’s supply comes from micro data centers and neo cloud partners, renting racks under 3–6 month contracts that are negotiated individually. This alone provides a surprisingly diverse but high-quality fleet: RTX 4090s, 5090s, Pro 6000s, H100s, H200s, B200s, B300s, even early exploration into AMD GPUs and niche accelerators like AWS Trainium, for which Yotta has begun open-sourcing custom performance-optimized kernels.

But the real shift is what comes next.

The team plans to move from this contract-heavy model to a self-serve supplier platform, where:

individuals

micro data centers

boutique hosting clusters

and neo cloud partners

can plug their GPUs directly into Yotta with minimal human involvement.

This changes the supply economics entirely. Instead of negotiating each deal, Yotta becomes a distribution channel. Supply can expand when demand heats up and shrink when it cools. It is the difference between owning a taxi fleet and running Uber.

And it fits Yotta’s technical worldview perfectly: a system designed to harness whatever hardware shows up.

Where the Demand Comes From

Demand expands as price falls.

The hook is simple: teams get more usable throughput per dollar because the system keeps GPUs busy and avoids the problems that normally bleed performance out of distributed setups.

Yotta’s internal benchmarks show this clearly. GPU costs are often 50-80% cheaper than AWS’s on-demand GPU pricing, because current clouds are inefficient in routing and avoiding hotspots. Better scheduling, better utilization, and access to cheaper hardware mean engineers spend less time babysitting infrastructure and more time building. A win-win!

But cheap only works if the product is good. Yotta understood that early, which is why their go-to-market strategy started with building technical credibility rather than racing to onboard customers. Much of their early energy went into research partnerships, community experiments, and HPC-grade performance work.

This includes powering EigenAI’ GPT-OSS initiative and participating in developer challenges that stress-test distributed systems in real conditions.

A few examples stand out:

AMD Developer Challenge 2025: Yotta won first place by building high-performance implementations of All-to-All, GEMM-ReduceScatter, and GEMM-AllGather kernels on the MI300X, achieving major throughput improvements through kernel fusion and ROCm-specific optimizations.

Reinforcement Learning Breakthrough: By tuning 3D parallelism with Verl, Yotta demonstrated a 4.3× faster RL rollout and a 72% shorter training cycle on MI300X hardware. This wasn’t achieved by adding more GPUs, but by orchestrating them efficiently.

Heterogeneous Hardware Breakthrough (AWS Trainium): On AWS Trainium, Yotta’s research team built NeuronMM, a custom matrix multiplication kernel for LLM inference that delivers 1.66× higher end-to-end throughput (up to 2.49×) than AWS’s own Trainium baseline, without changing hardware.

The gains come from software: reducing data movement across Trainium’s memory hierarchy, maximizing on-chip SRAM utilization, and aligning tensor layouts to the accelerator’s physical architecture. In other words, Yotta extracts more performance from the same silicon by understanding how it actually behaves.

This research-first posture served two purposes.

It proved that Yotta’s architecture holds up at the limits. And it built trust with developers and researchers who actually care about performance instead of marketing. In a field full of exaggerated claims, Yotta chose to show its work.

Even with this research focus, customer demand didn’t wait on the sidelines.

Yotta is already running 10+ paid business pilots, all of them using the system for production workloads. These include video upscaling applications, image editing pipelines, and intelligent hiring systems, use cases where both throughput and reliability matter.

Since launching in May 2025, these customers have collectively generated over $2.3M in revenue within the year, translating to a ~$7M ARR run rate for Yotta. For a company still early and not yet permissionless on the supply side, this level of revenue is a strong signal of pull.

So where does demand grow from here? In my view, it starts with the early adopters who are price-sensitive and have limited access to hyperscaler GPUs.

AI Startups: They are building from scratch and yet not locked into the hyperscaler ecosystem. They are also cost-sensitive. Inference at scale is expensive, and reasoning models can demand 5-25x more compute, which makes a cheaper, high-performance alternative hard to ignore.

Academia and Open-Source Communities: Researchers, Labs and grassroots model builders are chronically compute-constrained. Partnerships like the one with EigenAI and SGLang suggest that open-source groups see Yotta as accessible infrastructure for experimentation.

Web3 Builders: They care about verifiable compute and will gravitate toward systems with decentralized assurances and cloud-level performance.

Enterprises will take time (longer sales cycle) but likely to follow close behind. Many AI prototypes are already turning into production systems. Most teams will not rip out AWS or Azure, and many are locked into long-term contracts anyway. What they need is overflow capacity and more predictable inference costs. That creates a natural role for Yotta as a second compute pool that absorbs pressure from the first.

Even more interesting is OptmuX. As an orchestration layer, it can plug into existing hyperscalers and manage resources across them, applying the same optimizations without forcing enterprises to change where they buy their core compute.

I believe that as AI usage expands and compute becomes a constraint, platforms that can be at the Pareto frontier of performance, flexibility, and cost will be the only ones that can actually take market share from the giants.

It’s a hard fight, of course, but Yotta is positioning itself to be one of them.

Business Model: Optimization First, Compute as Distribution

To understand how Yotta makes money, stop thinking of it as "renting decentralized GPUs." Fundamentally, Yotta could be viewed as an arbitrage engine.

The economic thesis is straightforward: pristine compute from AWS or GCP carries a brand premium and scarcity markup. Messy compute from gaming rigs, micro data centers, or crypto miners trades, neo clouds at a steep discount because of perceived reliability risk.

Yotta’s business is software that bridges that reliability gap, turning messy compute into infrastructure that behaves predictably enough for real workloads. So it captures the spread between raw compute costs and what customers are willing to pay once risk is reduced.

In practice, this resolves into three distinct revenue lines, each with very different economics.

Revenue line #1: Serverless & Compute Layer

Yotta aggregates GPU capacity from micro data centers and underutilized hardware from neo cloud partners, and exposes it through a serverless, elastic compute layer that behaves like enterprise-grade clusters. This enables faster startup times and significantly lower costs than hyperscalers such as AWS.

While gross margins in this segment are structurally thinner (estimated at 20–30%), the strategic value is substantial. Every workload executed through the Serverless & Compute layer generates high-fidelity system telemetry, including scheduling outcomes, hardware-level performance variance, failure modes, and cost–latency trade-offs across regions and GPU types.

This real-world execution data continuously feeds OptimuX, Yotta’s optimization engine, improving its ability to make intelligent, system-level decisions across increasingly complex environments.

Strategic role: Serverless & Compute is Yotta’s execution layer and data flywheel, powering learning, optimization, and long-term defensibility.

Revenue line #2: Model APIs (with Intelligent Model Routing)

On top of raw compute, Yotta offers production-ready Model APIs that host open-source and custom models with built-in Intelligent Model Routing. Incoming requests are dynamically routed across models, regions, and hardware backends based on latency targets, cost constraints, availability, and real-time performance signals.

This business is volume-driven and carries higher margins than raw compute. More importantly, it is Yotta’s wedge into high-frequency production inference inside enterprises. By abstracting away infrastructure and model choice, Yotta lets teams ship AI features with minimal operational work, while the system continuously optimizes in the background.

Model APIs also create a natural upgrade path:

From single-model endpoints → multi-model routing

From static deployments → adaptive, performance-aware inference

From API usage → deeper adoption of Yotta’s control plane

Revenue line #3: Managed Control Plane & OptimuX Orchestration software

This product is still in development, but the plan is clear. Yotta wants to offer enterprises a managed AI control plane (powered by OptimuX) that orchestrates workloads across AWS, Azure, on-prem clusters, and alternative cloud providers, without forcing customers to migrate their infrastructure.

This is a pure software (SaaS) business:

No hardware ownership or balance-sheet risk

High gross margins (60–80%+)

Strong retention driven by deep system integration

Once OptimuX is responsible for routing production workloads like deciding where and how models run based on cost, performance, reliability, and policy, switching away requires a full re-architecture of the ML and inference pipeline, creating substantial lock-in.

Over time, the control plane becomes the system of record for AI execution decisions, positioning OptimuX as the operating layer for enterprise AI infrastructure.

Long-term: The Managed Control Plane and OptimuX orchestration layer will be Yotta’s primary revenue driver and the foundation of long-term platform defensibility.

Where Defensibility Actually Comes From

We know GPU supply is not a moat.

Operators with H100s or 4090 rigs will use whichever network pays them the highest rates today. If io.net offers better utilization or Aethir offers better rates, supply migrates overnight. Commodity hardware rental has zero loyalty.

This means Yotta's defensibility cannot live on the supply-side. It has to come from demand.

The real moat is data, and it comes from the Intelligence Loop. To me, it's the strongest technical argument for why this business could work long-term.

By running AI workloads across thousands of heterogeneous and unreliable GPUs, Yotta generates a proprietary operational dataset that hyperscalers never see: how GPUs and models behave under imperfect conditions.

AWS and GCP don’t encounter these dynamics. Their environments are deliberately sterile: identical hardware, identical networking, identical cooling. They optimize for consistency, which means they never learn how to manage chaos.

Yotta does.

Every failed job, thermal spike, and network hiccup feeds back into the OptimuX optimizer, improving failure prediction and adaptive routing. The messier the hardware Yotta manages, the smarter its orchestration software becomes.

This creates a data moat in operational knowledge. Eventually, Yotta could become the only platform with enough real-world evidence about how to reliably run high-performance AI on low-cost, heterogeneous infrastructure.

That's defensible.

What Comes Next

2026 is crunch time.

Yotta’s next milestone is to get OptimuX fully operational by Q2 2026 and spin up the telemetry engine that feeds real-world performance data back into the optimizer and scheduler. By the end of 2026, the goal is a fully operational permissionless GPU compute network, open to anyone who wants to contribute hardware, not just curated partners.

Long-term, the vision is full autonomy. The infrastructure uses its own idle cycles to train the optimization models that govern it, becoming self-improving as operational data continuously refines scheduling decisions without human oversight.

The Team: Research + Industry as a Real Edge

Decentralized compute sits at an awkward intersection: GPU research, distributed systems, and the unglamorous work of making things run outside a paper or a lab. Most teams are lucky to have real depth in one of those areas. Very few have all of them. That is why so many struggle.

Yotta somehow landed both.

Daniel Li’s (CEO, Co-Founder) through-line was always compute. He started as a GPU engineer at Sony’s U.S. research lab, back when NVIDIA chips were still “graphics cards”. Then came Meta, where he worked on infrastructure, privacy, and transparency systems for Facebook and Instagram. Those systems had to function at a planetary scale and be perfect. Nothing teaches you respect for reliability like owning the thing that breaks when a billion people refresh their feed.

By the time Daniel joined Chainlink Labs to lead CCIP, he had seen what modern infrastructure looks like when you zoom out. Different networks, different architectures, different incentives. Everyone assumes someone else will make it work together.

Daniel observed that inference costs were spiraling. Serving large models was so expensive that companies were losing money on every request. He told me some teams were eating $2 in GPU costs to generate $1 in revenue. That’s not a real business model.

The problem, as Daniel saw it, was not raw scarcity. It was inefficiency and fragmentation. Enterprises had compute spread across clouds, regions, and vendors, with no intelligent layer to coordinate it. So he left to build that layer. Every stop along the way, from Sony to Meta to Chainlink, had pointed to the same conclusion: compute scarcity is mostly a coordination failure.

That idea didn’t stay a sketch for long. Daniel needed someone who lived at the edge of what GPUs can do, someone who spent their career squeezing performance out of hardware that everyone else treated as a black box.

Enter Dr. Dong Li.

Dong leads the Parallel Architecture and Systems Lab at UC Merced, co-runs its HPC systems group, and has done time at Oak Ridge National Lab, one of the few places where “large-scale compute” really means large. He even headed an NVIDIA GPU Research Center, which is as close as academia gets to the factory floor of GPU innovation.

His research hits every pain point Yotta wants to eliminate: out-of-memory execution, fault tolerance, heterogeneous memory, training efficiency for giant models. Some of his ideas have already made it into Microsoft’s DeepSpeed, which is a quiet tell that you’re doing more than writing papers. You’re shaping the stack.

Where Daniel saw a system-level failure, Dong saw the physics: GPUs were getting faster, but moving data between them wasn’t. Distributed training was bottlenecked not by math, but by communication and memory movement.

But there was still a missing piece.

Knowing what should happen and why it was failing was not enough. Someone had to actually build the systems that turn these ideas into production-grade infrastructure, systems that real developers could use, at real scale, under real constraints.

That’s where Johnny Liu comes in.

Johnny (CTO, Co-Founder) has spent his career turning ambitious AI research into systems that actually survive production. At Amazon, he led engineering and science teams behind Amazon Rufus, one of the earliest large-scale, GenAI-powered shopping assistants. His work spans foundation model training, agentic reinforcement learning at DeepSeek R1 scale, and some of the most demanding data pipelines in the industry, processing internet-scale data and real-time customer signals.

Before Amazon, Johnny was at TikTok, where he founded and led several of the company’s key infrastructure efforts. He was an early internal champion of Ray for NLP at ByteDance and later led the creation of KubeRay, now the official Kubernetes-native solution for Ray in the open-source ecosystem. It’s one thing to build infrastructure for a single internal use case; it’s another to generalize it into an industry-standard platform. Johnny has done both.

Across roles, his focus stayed consistent: systems for AI. At ByteDance, he led ML-driven auto-tuning efforts like Spark AutoTune to cut resource waste across thousands of production jobs. He also built RayRTC, TikTok’s first serverless NLP platform, dramatically reducing training time and GPU idle rates while improving developer productivity across hundreds of ML teams.

Earlier in his career, Johnny worked at Berkeley Lab on large-scale training and data analytics on supercomputers with thousands of nodes. He has published extensively across top AI and HPC venues and has served as an NSF and Department of Energy panelist since 2015, reviewing and funding work at the intersection of AI, systems, and high-performance computing.

If Daniel brings the instinct for operating systems at continental scale, and Dong brings the ability to push GPUs to their physical limits, Johnny brings the discipline of turning both into production-grade infrastructure.

That’s where the perspectives lock together.

They are trying to rewrite how compute gets coordinated across clouds, across architectures, across everything.

It’s rare to see a team this well-matched with the shape of the problem. Rarer still to realize the problem has been following them for most of their careers.

Fundraising - $3.5M

Yotta’s earliest and most credible validation came not from the venture market, but from the U.S. national research and strategic computing initiatives.

In 2025, NSF awarded Yotta a $300,000 SBIR grant to support the development of a decentralized operating system for AI compute, following a rigorous, peer-reviewed evaluation process conducted by experts in distributed systems, high-performance computing, and large-scale infrastructure.

US NSF SBIR funding is designed to identify technically non-obvious, execution-intensive systems that are strategically important but often poorly understood by traditional capital markets at early stages. So the award has positioned Yotta as part of a broader national conversation around strategic compute infrastructure. It’s adjacent to initiatives such as the American Science Cloud and federally backed efforts to modernize AI and HPC foundations.

In hindsight, institutional recognition arrived first from those structurally equipped to judge deep infrastructure work, well before VC interest.

From the outset, Yotta was intentional about its fundraising strategy. The team deliberately crafted an unusually technical pitch deck and business plan, emphasizing low-level systems design, scheduling, memory offload, and distributed execution. This was a conscious choice to filter for investors with the technical depth to truly understand the problem space and align with the team’s long-term vision.

As a result, many generalist investors filtered themselves out. The process was less about broad outreach and more about alignment. Investors who could engage deeply with the technical substance were the ones who consistently leaned in and wanted to lead.

The team took that as a signal that the strategy was working and that partner quality was improving. In the end, several technically strong funds were interested in leading, and Yotta went with two of them as co-leads for its first institutional round.

The company raised a $3.5M round co-led by Big Brain Holdings and Eden Block, with participation from Mysten Labs, KuCoin Ventures, Generative Ventures, and MH Ventures.

Our Thoughts

The Bullish Case

The game for Yotta is whether it can truly automate work that companies currently pay very expensive experts to do manually. That’s an important wedge for any AI startup.

Today, optimizing GPU workloads across mixed hardware is still a craft skill. You hire kernel engineers who cost $300K to $500K a year, or you bring in HPC consulting firms to tune performance one workload at a time. That market is already large, ~$40B+ annually, and it keeps growing at 7%.

Yotta's OptimuX automates this work. It's the same pattern as Terraform (automated infrastructure consulting) or Databricks (automated data engineering).

The realistic outcome would be that Yotta becomes the go-to solution for workloads where 30-40% efficiency gains matter enough to justify switching.

If Yotta captures even 5-10% of the GPU optimization consulting market over 5-7 years, you are looking at $500M — $1B in potential ARR. Of course, that outcome is by no means guaranteed and depends on a few things going right.

First, it needs proof at scale that production workloads can run cheaper without sacrificing reliability. Second, it needs real enterprise stickiness, a small number of customers spending $2M or more per year who would find it painful to rip Yotta out once it is embedded.

That is the opportunity. Automate expensive, specialized work and take a slice of the consulting budget. Not overthrow hyperscalers.

Yet Another Decentralized Compute Protocol?

I know you’re asking - do we really need another "decentralized GPU marketplace”? It’s a crowded space. For most investors, they blur together.

The typical DePIN playbook is to aggregate idle GPUs, launch a token, build a marketplace, and market it as "democratizing AI." The problem is that none of this solves coordination. Aggregating GPUs is easy, but making them perform coherently is hard.

This is why decentralized networks attract only fault-tolerant workloads (rendering, batch jobs), and not production AI inference.

What makes Yotta different:

Demand before supply: $7M ARR proves real demand exists before opening permissionless supply

Performance parity: Within ~15% of centralized clusters

My view is that the enterprises paying for AI infrastructure probably don't care where GPUs come from. They care about cost and performance.

The real differentiation is not "we're decentralized." It's "we make distributed GPUs perform like centralized infrastructure." That's a technical moat (strong) rather than an ideological one (weak).

Positioning alone does not create defensibility. Yotta still has to prove that performance holds as complexity rises, with more customers, larger models, and increasingly heterogeneous hardware.

The gap between "10 enterprise pilots → $7M ARR" and "100+ customers → $100M+ ARR" is the chasm that most new infrastructure companies fail to cross. Whether Yotta can clear this, it’ll be obvious in the coming months.

Conclusion

AI has long been shaped by the physics of the data center. Identical hardware. Carefully controlled environments. That model is already cracking. Compute is fragmenting across clouds, regions, suppliers, silicon types, and millions of underutilized machines.

Yotta’s bet is simple and hard. Do not fight fragmentation. Instead, lean in and build software that thrives in it.

If Yotta succeeds, decentralized compute will not feel radical. It will feel boring. Boring the way electricity feels boring. Invisible, dependable, everywhere.

In that world, the question stops being who owns the biggest data center. It becomes who controls the operating system that makes all GPUs work coherently.

Yotta is building the coordination layer for the age of distributed intelligence. And if they get it right, they may just erase the gap with centralized compute.

—-

Notes: The name Yotta is a statement of scale. Today’s frontier is exascale, 10¹⁸ FLOPS. Yotta Scale is 10²⁴, a million times larger.

You cannot build a yottascale computer inside a single data center. The power density would melt the grid. The only way to reach that scale is by coordinating the latent, idle silicon spread across the planet.

Thanks for reading,

Teng Yan and 0xAce

Useful Links:

If you enjoyed this, you’ll probably like the rest of what we do:

Agent Angle: Weekly AI Agent newsletter

Decentralized AI canon: our open library and industry reports

Disclosure: This essay was supported by Yotta Labs, which funded the research and writing.

Chain of Thought kept full editorial control. The sponsor was permitted to review the draft only for factual accuracy and confidential information. All insights and analysis reflect Chain of Thought’s independent views. Where tradeoffs or limitations exist, they are stated clearly.